The picture is complex. How can you make the best choice?

The choice of alternative fuel depends on the mission profile. Global carbon emissions, including emissions created by the shipping industry, must be cut significantly in the coming years. Most of the emissions produced by this industry originate from fuel consumption. For all vessel types, it is crucial to understand and evaluate the operational aspects of the vessel versus the consequences of the choice of fuel types.

When designing sustainable vessels, one must consider reducing energy consumption, using greener energy sources and materials, operating more effectively, and using energy smarter onboard.

In this article, we focus on using greener energy sources.

Use of greener energy sources

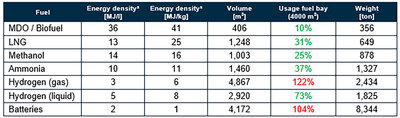

As ship designers, we evaluate alternative fuels with our clients and design the vessel's power system. Studies of power need, range, sailing route, and fuel availability, the realisation timeline combined with the availability and readiness of equipment and technology, the approval process, and the customer's expectations and strategies are all aspects that the ship designers will conduct with the customer. In particular, the volume and energy intensity of the different fuels must be evaluated. This might drive vessel size and operational range/endurance.

This article is based on one of Ulstein's studies on alternative fuels, which used the typical mission profile of heavy-lift installation vessels used for the foundation installation of offshore wind turbines.

Comparison of different alternative fuels

The setup below is divided into Emissions, the benefits and/or downsides regarding Safety (flammability and toxicity) and Maturity (technologically, cost of energy and bunkering availability).

Marine Diesel Oil (MDO) is today's widespread choice, but it is also yesterday's choice. The carbon footprint is too large to continue using this fuel as the sole choice for the future.

When considering alternatives, it is difficult to determine which fuel will be the sound choice. No single solution is viable for all vessel types, and evaluations of the earlier-mentioned criteria need to be done for each project. Looking into possible future needs and scenarios is also an important part of this.

Alternative fuel study for heavy lift installation vessel design

A heavy-lift installation vessel is a sizeable asset, driven by stability and deck area requirements. Because of its dimensions and layout, it is possible to identify spaces in the vessel to install dedicated tanks for alternative fuels.

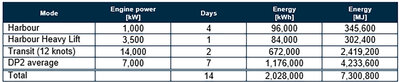

Studying the typical mission profile for one of our heavy-lift installation vessel designs (the ULSTEIN HX118), we find the amount of energy needed for the typical operational modes and the duration of each mode.

Noting that a typical mission cycle in this example lasts for approximately 14 days, and having implemented an alternative fuel tank in this vessel, we can now look at the various fuel options and the usage of the fuel tank (numbers in green/red).

From the table above, it can be concluded that all alternative fuels are theoretically feasible for the Heavy Lift Vessel (if hydrogen is assumed as liquid storage). The calculated mass of the alternative fuels is significant but controllable within the vessel's loading conditions; the expected loss in deadweight capacity is negligible.

The reference full-electric vessel, with 14 days of operation, would require a very large battery, which is impractical from both a weight and cost perspective (very expensive ~200M$). However, full-electric battery operations can be feasible for short periods.

But other aspects are not so straightforward. For many of the alternative fuels the marine industry considers, regulations (and therefore readily available and approved technology) are not yet in place.

LNG:

The most low-hanging fruit with respect to regulations is LNG, where bunkering infrastructure is also currently getting sufficiently in place. The downside is that it is still a fossil fuel.

METHANOL/AMMONIA:

Although regulations are now available for methanol and ammonia, they are still considered alternative design processes that require risk-based case-to-case approval processes to be performed.

HYDROGEN:

For hydrogen, regulations are not yet set for IMO regulated vessels, and the alternative design process will be even more time-consuming.

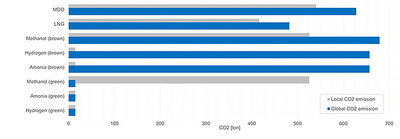

When evaluating fuels, the real emission reduction must be assessed, as exemplified in the figure below.

CO2 emissions for a typical mission cycle:

Green = produced from renewable energy and including carbon recapture.

Brown = produced from fossil fuels.

Hydrogen and ammonia result in no or very low local emissions. However, for global emissions, methanol and hydrogen/ammonia must be green to produce very low emissions. Brown/grey methanol and black hydrogen/ammonia have higher global emissions than the other fuels investigated.

A clear path has not yet been laid for hydrogen, ammonia, and methanol. Only one will most likely be adopted by the market majority, and the others will most likely stay in the niche market.

For all the different fuel types, it requires that the ship and its design, the integrated equipment, systems and technologies, system approval, production and availability of the fuel itself, logistics, and bunkering are in place. On top of this, there are the commercial aspects.